EV engineers used Video Transport for virtual conference production

The e-gnition Hamburg club is a group of students at the Technical University of Hamburg competing in Formula Student, the largest engineering competition for students in the world, where up to 500 student teams from around the world design, build, test, and race small-scale formula-style racing cars. We had an inspiring conversation with Nils Albrecht, engineer and former leader of the e-gnition Hamburg driverless team, about how Video Transport was used to produce a virtual conference in 2021.

The student design competition originates from the U.S., where it was first held by the SAE student branch at the University of Texas at Austin in 1980. The concept of the competition is that a fictional manufacturing company contracts a student design team to build a prototype of a small Formula-style race car, which will be evaluated for its potential as a production item. Since 2011, the focus has been on building electric race cars, and since 2017, it is also driverless – fully autonomous race cars.

The competition is about getting engineering students to gain hands-on experience by building a race car within a one year timeframe… When it started in the US, it was more like a thing for students to have fun building something in their garage. But right now it's so advanced, the cars are really crazy – especially in Germany, where it is really popular because of our automotive industry.

Although focused on racing, the car designs within the competition have always been ahead of what the industry was doing. When the first EV cars were created back in 2017, they were a little bit more advanced than what most car manufacturers were selling. The world record for the fastest accelerating electric car is still held by AMZ Racing, a student team from Switzerland: 1.513 seconds to reach 100 kph (62 mph), slashing about a quarter of a second off the previous record time – 1.779 seconds set by a team from the University of Stuttgart the previous year. The car has been built by 30 students, and almost all of the car's parts have been custom built (apart from tyres, battery cells and the motor control units).

The competition also serves as a technical and talent laboratory for the automakers, who support competing teams by supplying parts and sponsoring. In the automotive industry, participation in the competition counts as business experience – since it is not just hands-on experience with a complex technical project, but also the project management behind it (imagine a self-organised team of 50-70 students).

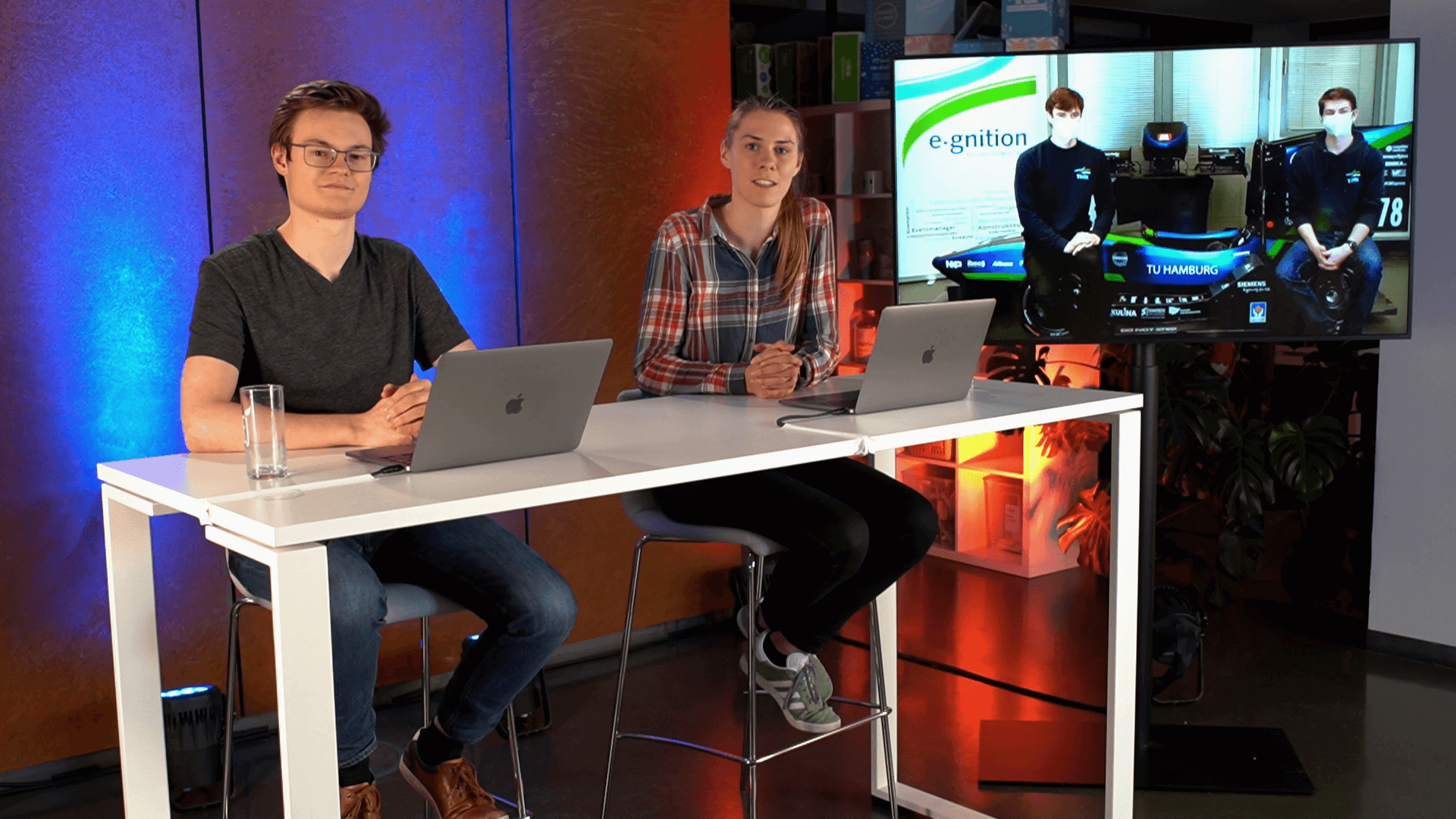

After building three cars and being team leader for one year, Nils went back to his studies, but remained to be one of the main organisers of a conference that brings competing teams together and serves as a networking platform for about 250 participants. This time, because of the restrictions, the conference could not be held in Hamburg in its traditional form, so a virtual event had to be organized instead.

In 2020, the Formula Student competitions, traditionally held every year and being big events all over the world, were cancelled. Team leaders from nine different teams were invited to discuss how they handled the situation.

We picked some teams we thought might be interesting for the content of the show. We knew that in Norway, for example, the restrictions were really hard: they were not even allowed to access the workshop. So we invited the guys from Norway to ask them how they dealt with the situation.

Having looked around for a way to integrate nine external guests into a live stream, Nils selected Video Transport as the go-to solution. VT was responsible for transporting the video streams from the remote guests (connecting via the web guest feature) to the main video mixer.

None of us had ever done something or something even comparable to this. We are students who build race cars. None of us has ever had video production experience at any point… We tried the usual Zoom things and all the video conferencing tools, but they were not delivering the quality we were hoping for.

An improvised studio was built in an office, where the team gathered on weekends to work on the production. A total of 2 computers were used in this production:

- four local camera feeds were fed into a computer running vMix;

- a computer running Video Transport delivered the return feed to nine remote guests, received their web guest feeds and made them available for the vMix machine via NDI.

In order to have proper mix-minus for each of the guests, a hardware audio mixing console was used.

I think we are really happy with how everything turned out. It just worked. All the guests that have joined us were really happy with the web interface. And it just worked on all computers and all browsers, so we didn't have any trouble on that side.

Four people (all of them engineers) were involved in operating the setup and orchestrating the production: the production director, the technical director (operating the vMix instance), one person operating the audio console and one person responsible for Video Transport (communicating with the guests and checking their connection to Video Transport).

We liked the flexibility of Video Transport. There are a lot of parameters to set up. You can set video encoder, bandwidth, latency. It is much more flexible than other solutions… What was really beneficial, I think, is the hardware decoding for web guests on the GPU. Because encoding and decoding nine VP9 streams on one machine is terrifying.

With Video Transport it was possible to receive high-quality video and audio from each of the guests and operate each stream separately – as if it were a camera feed.

It was nice to have something a lot more professional than just using Zoom calls. It's really nice to have one machine where all the guests are concentrated: you can see who's online, you can see preview feeds, you can see connection details. This is a lot easier to overview compared to nine Zoom calls to nine external guests. It would be just too hard to monitor all of them at the same time.

Finally, I asked Nils how they figured all of this out without any prior video production experience. His answer was obvious:

We're engineers.